Genre: Non-fiction/Social Science/Crime – My rate: 5 stars!!

Genre: Non-fiction/Social Science/Crime – My rate: 5 stars!!

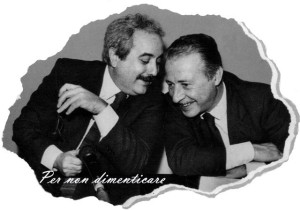

This gripping and intelligent book of ‘true crime’ recounts not just the decade-long campaign by the 2 magistrates and friends Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino to break the back of the Sicilian Mafia; It’s not simply a Bittersweet bio-pic pays tribute to these two colleagues grown inside the hideout of the cruelest Mafiosi, now high level businessmen years later.

Excellent Cadavers is a useful narrative device, given that most people aren’t familiar with the many names involved in the story mafiosi and politicians alike). The story gives a brief history of the mafia, but it focuses on the 1980s and early 1990s; A crime Lord, Tommaso Buscetta, gave the police and the judges a definition of terms and a clearer picture: “The word ‘mafia’ is a literary creation, while the real ‘mafiosi’ call themselves simply ‘men of honor’…and the organization as a whole is called the ‘Cosa Nostra’… every man of honor belongs to a family…at the head of each family there’s a ‘capo’ elected directly by the men of honor. He, in turn, selects a ‘sotto-capo’ (underboss) and one or two ‘consiglieri’ (counselors)…” And so on.

There are 3 groups of antagonists in this book, who are all different types of parasite.

First, the Sicilian mafia. This book describes in detail the many ways the mafia was a parasite on southern Italy, by driving out industry and by misdirecting government investment in the region.

Second, the Italian politicians who were either involved with the mafia or who wanted weak laws because of their own illegal activity (if you are taking bribes, even if you are not involved with the mafia you will want an ineffective justice system).

Third, the Italian judiciary. Members of this last group, who appear to have been the majority at least before the deaths of Falcone and Borsellino, thought it was more important to protect seniority rights to positions than to have competent people filling them.

These two prosecutors stand out for their honesty, discipline and professionalism. They and some of their colleagues represent the possibility of a rational, modern approach to law and civic life, something that has not always flourished in Italy.

Their attempts to fight the influence of the Mafia — and to curb violence that in the early 1980’s was claiming three lives a week in Palermo — were often obstructed by longstanding traditions of red tape and outright corruption.

Amidst its lawlessness, Falcone and Borsellino put together the Palermo maxi-trial, a titanic anti-mafia case that required the construction of an elaborate concrete bunker courtroom and ultimately led to an incredible 344 convictions. It was, Stille writes, “a telling indication of the upside-down nature of life in Sicily on the eve of the maxi-trial: mafia fugitives moved freely about Palermo while government prosecutors had to live in prison for their own protection.”

The two judicial investigators not only sent hundreds of gangsters to jail, they also exposed Mafia corruption of national political leaders that led to the indictments of two of Italy’s best-known politicians, Bettino Craxi and Guilio Adreotti.

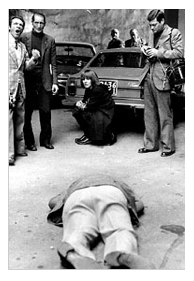

Falcone was maneuvered out of his position in Palermo and ultimately assassinated; Borsellino was killed six months later. But their death lead to their greatest triumphs, for their murders awakened a nation to the corruption of the ruling Christian Democrats and caused the downfall of Italy’s First Republic.

It was hard to believe how much terror and power the corrupted few could inflict on a whole country.

Time magazine named Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino among the 60 All Time Heroes of the 20th Century–and well deserved. I highly recommend this book to anyone looking for modern heroes, so desperately needed in a cynical, skeptical world where a man’s character, courage and honesty can only be ultimately proven until his assassination, as described by Stille.

Mr. Stille serves as narrator and tour guide, taking us to the scenes of crimes and explaining their causes and consequences.

Mr. Stille does not dwell on the Mafia as a historical or sociological phenomenon, emphasizing its dysfunctional relationship with the postwar Italian state rather than its older roots in Sicilian culture. His Mafia is not the colorful, violent flowering of ancient Mediterranean peasant customs, but rather a thoroughly vicious organization bent on the subversion of democratic norms and the brutal elimination of anyone who dares to oppose its ambitions.

The author, more reporter than historian, does not stray too far beyond the immediate parameters of his main story, but the strongest criticism to be made of this book is also the highest praise: you wish there were more of it. This is not only because the details are fascinating in their own right, but also because this quintessentially Italian tale is, more broadly, a case study in the difficulties involved in maintaining an independent and secure legal system.

Despite new leadership in this country of great wines, world-leading design, highest level of Art, cuisine and landscapes beauty, the pattern of history as outlined by Alexander Stille would seem to say that Italy is destined to live with the untouchable assassinations on its streets and the corruption that seems always to rule these corridors of power.

The wonder isn’t that these excellent prosecutors were eventually murdered (in 1992), but that they survived as long as they did under the threat of such lethal enemies long enough to do some good and give their citizens a taste of justice. One cannot offer too much praise for these men and the many other courageous Sicilians who also were murdered in their efforts to bring justice to Sicily.

The conclusions Mr. Stille reaches are mixed. The aftermath of Mr. Falcone’s and Mr. Borsellino’s deaths was a wave of popular revulsion against the Mafia, and a belated cleansing of the political system.

But then the rise of Silvio Berlusconi, who became prime minister in 2001, led to the systematic disempowering of the judiciary system and the repeal of legal instruments (like the Italian witness protection program) that Mr. Falcone and Mr. Borsellino had fought for.

The book, like the documentary that followed, ends on a pessimistic note, with a reminder that the romance between criminals and politicians may have cooled, but has not ended.

Valentina Caprio